A STUDY ON THE ALLIANCE OF SAHELIAN STATES (AES)

Accra Centre for Applied

Research Study Report No. 8

ALLIANCE OF SAHELIAN STATES

2024

Prepared by the staff team of ACAR

April 29, 2024

All enquiries should be channeled to:

The Head of Research, #96 George Walker Bush Highway,

North Dzorwulu, Accra. Ghana

All rights reserved. No part of this report may be cited

or reproduced without a written permission of ACAR.

ALLIANCE OF SAHELIAN

STATES – A STUDY

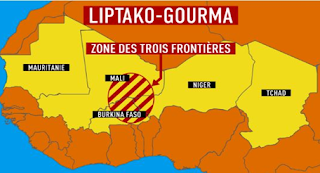

The AES Region- Sketch

Abstract

In the last four years for instance, there had been

seven successfully prosecuted military coups d’états in Guinea (2), Mali (2),

Burkina Faso (2) and Niger (1). In addition to these military interventions,

there were occasions of numerous manipulations and undermining of the

constitutions in Senegal, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Mali, Burkina Faso and

Niger led by democratically elected incumbent or sitting civilian governments

who sought to change the basic laws of the land in order to entrench themselves

in power. In most instances, these had resulted in disastrous social and

political consequences. Some of these reflections could be seen as fractious

contestation for power, constitutional coups d’états and weakening of the

neocolonial states.

From the commonality of issues facing

West Africa, it is abundantly evident we would require deepening our knowledge

and understanding the contentious issues at the regional level. Furthermore,

the territories of the Alliance of the Sahelian States (AES) are populated by

numerous marginalized indigenous peoples such as the Mbororo-Bororo/Wodaabe in

Mali, Tuareg and the Tuhu-Teda/Daza in Niger. The historical obsessions of

these peoples towards protection of their pre-colonial space and asserting

their rights to traditional nomadic way of life are believed to be one of the

destabilising factors within the Sahara-Sahel region. This has to be studied

comprehensively and understood if peace were to be restored into the

Sahara-Sahel in particular and West Africa in general.

During 2023, ACAR with the assistance of a team of researchers conducted

extensive desk research covering sixteen West African countries[1].

This report however focuses on the AES countries. It applies the methods of

historical analysis including drawing from appropriate sources as well as

information from contemporary authorities to examine the origins of the crises

faced within the AES.

Introduction

The spate of “anti-imperialist coups des états[2]”

in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger was the direct result of massive civil

dissatisfaction over the poor handling of the armed insurrections by the

respective civilian governments. It

would be recalled that from the start of 2022, these countries continually

experienced increased jihadists insurgency and non-state armed groups attacks

particularly within the Liptako-Gourma Area. These attacks were followed by

extensive population displacements despite interventions from the French

Legionnaire, United Nations’ peacekeepers and the siting of several foreign

military bases within the Sahel area.

To take sovereignty into their own hands, Mali,

Burkina Faso and Niger signed a military and mutual economic pact to constitute

themselves into an Alliance of Sahel States (AES)[3].

This Alliance presents them an opportunity to break out of the neocolonial hold

of the metropolis, take a different path of development while riding on

anti-French imperialist sentiments and to emerge as an alternative pole[4] to

ECOWAS. Additionally, as members of the AES, they will able to harness their

synergy to secure mutual security against the jihadist insurgency.

At the close of 2023, the AES countries have fully

broken diplomatic and economic ties with France including defence accords and

expelled France[5] from the various

territories including the latter’s military bases. In March 2024, Niger- one of

the constituent members of the Alliance- has also refused to renew the lease of

United States’ largest air drone base and asked for its closure. As of now, the

AES countries have moved closer to Russia which has signed mutual economic,

defence and security pacts with each member country. The latter is also known

to be assisting Burkina Faso to build a nuclear facility.

This essay seeks to provide a platform for dialogue in

a push to build and promote a healthy exchange of information throughout West

Africa. The paper is divided into three related parts. The first part presents

an overview of the AES countries in terms of its geography (location, land

size, topography, climate, vegetation, etc.), extractive wealth, infrastructure

and production. It further addresses questions on political economy. The second part

delves into the current state of the conflict and the drivers of insecurity

particularly in the Liptako-Gourma, Boucle du Mouhoun and Ménaka Regions as

well as those of the subjective factors of social change. The last section

evaluates AES as a Pan-African

Union.

PART ONE

Geography

Location

and other Demographics

The landlocked countries

of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) share boundaries with Côte d’Ivoire,

Ghana, Togo, Benin, and Nigeria to the south, Chad to the east, Algeria and

Libya to the north and Mauritania, Senegal and Guinea to the west. It has

a contiguous land space of 2,784,415 km2 representing some 45.54% of

the total land area of

West Africa (approximately

6,114,862 km2) and an estimated population of 73,748,026 in 2023.

The latter constitutes 16.33% of the West African estimated population (443,437,966)

in 2023. AES is sparsely populated when contrasted with the rest of West Africa

which has an average population density of 72.52 persons per km2.

The corresponding population density for AES is 26.49 persons per km2.

Topography

The landscape of the AES lies wholly

within the geomorphology of the Sahel and Sahara. The dominating landscape in

the southern parts are typical undulating gentle peneplain with an average

elevation of 284m above mean sea level. This rises to high plateaux and

escarpments in the north and southeast and rugged hills in the northeast with

elevations above 1,000m. In the southwest are the Fouta Djallon Highlands. The

northern highlands, particularly those in Niger, are extensions of the Ahaggar

Mountains Range running from Algeria to the Tibesti Mountains of Chad. The

highest point on this range is Mount

Gréboun (1,944m). The sandy

regions extend from the desert zones of Mali’s north to Aïr in in the Nigerien Sahara. The plains are drained by

rivers Senegal, Niger, Black, Red and White Voltas. There are also large

reserves of underground water awaiting to be tapped.

Climate

The territory of the

AES lies within the hot semi-arid climate to that of the dry tropical desert.

In the southern parts, the climate is characteristically Sahelian with mean

diurnal temperatures hovering between 240C to 33.80C and

night temperatures falling to 160C. The unimodal rainy season lasting

from June to October, and a long dry season from November to April. The

recorded mean annual rainfall is between 600mm and 900mm. For the dry tropical

desert climate, the mean diurnal temperatures vary from 420C to 450C

dropping to freezing levels. The rainy season is brief and irregular around

250mm annually and largely influenced by the position of the Inter-Tropical

Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The cool dry season is however from November to

February. Annual groundwater recharged in the Sahara area is abysmally

low around 1 ~ 13 mm/a

owing to low precipitation experienced in this region of the AES.

Vegetation

The

steppes of the Sahel regions of AES usually have sparse vegetation with

low-growing grassland and tall herbaceous perennials of the savanna. The

dominant trees are the acacia tortilis, baobab and thorny shrubs. The desert

vegetation, on the other hand, is mainly made up of cacti plants, date palms,

ground- hugging shrubs and acacia. Short woody trees with water-conserving

features also predominate.

Peoples

and Language

The predominant linguistic group is the Songhai and

this language is spoken in the three constituent countries of AES. Other

linguistic groups consist of Hausa, Fula or Fulbe, Mande, Tamashek, Teda,

Mossi, and Gurunsi. Although many of the people speak Arabic as the common

lingua franca, French remains the language of business and commerce. The latter

is however spoken and understood by a small minority. The territory’s ethnic

groups correspond largely to the above-named linguistic groupings with Mande,

Mossi and Hausa ethnic groups being the predominant groups in Mali, Burkina

Faso and Niger respectively.

Overview of

Extractive Wealth

AES is very richly endowed in extractive wealth. Her

mineral resource endowment includes large reserves of uranium, gold, manganese,

coal, iron ore, tin, phosphates, and crude oil. Others are molybdenum, salt, copper,

lithium, limestone and gypsum. Her plant resources include the doum and palmyra

plants which provide wood for construction, dates, gums from acacia and kapok

trees. The latter is used for insulation, life jackets and so on.

The constituent states are also blessed with birds such as ostriches and reptiles (crocodiles and snakes) whose skins are extracted to make exotic handicraft for export to Europe. Despite most of her territory falling within the semi-arid climatic zone, it has the Senegal, Niger, Black, Red and White Voltas draining and watering its naturally endowed arable lands. AES is also home to a variety of wildlife that include elephants, lions, and cheetahs.

Mineral Wealth

The mineral wealth of the AES is extracted by major

international mining companies from France, Canada, Australia, South Korea,

Japan and China through fit for purpose subsidiaries. Niger’s uranium reserves[6] in Akokan, and Arlit, for instance, are currently mined

by ORANO[7] Canada; a successor to AREVA Resource Canada

Incorporated with its headquarters in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. Table 1

presents the capital structure and ownership of ORANO Canada. Its subsidiaries

in Niger are SOMAΪR, COMINAK and IMOURAREN. While SOMAΪR is wholly owned by

ORANO Canada, it directly or indirectly controls 34% of COMINAK and IMOURAREN

capital. Other shareholders of COMINAK are SOPAMIN, a Nigerien public company

(31%), Overseas Uraniun Resources Development Company of Japan (25%) and Enusa

Industrias Avanzadas S.A. of Spain (10%).

Table 1: Capital Structure of ORANO Canada

|

Shareholder |

% Holding |

|

French State |

56.31 |

|

CEA[8] |

35.70 |

|

Bpi[9]france Participations S.A. |

1.08 |

|

Total French State |

93.09 |

|

Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) |

3.13 |

|

EDF Group |

1.46 |

|

AREVA Employees |

0.70 |

|

Public |

1.32 |

|

Treasury Shares |

0.08 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

Source: https://cdn.orano.group; https://mscf.ca>orano canada - Jim Corman PDF, 17 April 2024

In spite of the fact that some 140,000 tons of uranium wealth had been

extracted by the ORANO Group between 1971 and 1922 from Niger and exported to

France and the European Union, the extraction never benefited the good people

and economy of Niger directly[10]. This is despite France being the historical buyer of

Nigerien uranium. France is not the only player in AES’ uranium mining. China

and South Korea are involved in the Azelik mine located some 200 kilometres

from Arlit. The Azelik uranium mine is operated by SOMINA a subsidiary of China

National Nuclear Corporation with 37.2% capital holding, SOPAMIN (a Nigerien

state mining company) – 33.0%, ZXJOY (a Chinese private company) – 24.8% and

Korean National Company (KORES), 5%.

Gold is the other important mineral wealth endowment of

the AES. This mineral is present in all the three countries with over 7 million

ounces of proven resources. The gold extraction industry serves as the largest

employer in Mali providing livelihood to some 2,000,000 people at the end of

2022. Industrial and artisanal[11] mining is carried out by foreign and local companies.

The major foreign multinational companies engaged in primary prospecting,

extraction and processing of gold ore are Barrick Gold Corporation[12], B2Gold Corp., and IAMGOLD Corporation. Barrick Gold

Corporation is based in Canada and known for the production of gold and copper

with mines in Mali (Marila/Loulo-Gounkoto[13]), Côte d’Ivoire (Tongon), Tanzania, Democratic Republic

of Congo, the Dominican Republic, Argentina and the United States. Its

ownership and capital structure are presented in Table 2.

B2Gold Corp[14], the other major multinational mining conglomerate, that

operates in AES (Mali), specializes in gold exploration and has mines in

Nicaragua, Namibia, and The Philippines while IAMGOLD[15], which owns and operates three gold mine concessions in

Burkina Faso (Essakane/Yatela/Sadiola Gold Mines), Suriname and Canada, is an

intermediate gold producer and developer. The structure of ownership and size

of capital holding of B2Gold Corp is presented in Table 3.

Artisanal gold mining, on the other hand, is largely

carried out by mafia-like criminals using small-scale unregistered small

companies and accounts for 10% of all gold production in Mali and Burkina Faso. One outcome of this is the influx of migrants

and child labour from the adjoining southern countries into the gold mining

areas of Mali and Burkina Faso. Owing to the absence of smelting and refining

facilities, much of the ore mined by both segments of the industry remained

unprocessed and un-refined prior to export[16].

Table 2: Ownership and Capital Structure of

Barrick Gold Corporation

|

Shareholder |

% Holding |

Citizenship |

|

The Vanguard Group, Inc |

5.617 |

United States |

|

Capital Research & Management Co. (World Investors) |

2.962 |

United States |

|

Wellington Management Co. LLP |

2.672 |

United States |

|

BlackRock Investment Management (UK) Ltd |

4.646 |

British |

|

First Eagle Investment Management LLC |

2.303 |

United States |

|

Flossbach von Storch AG |

1.880 |

German |

|

Fidelity Management & Research Co. LLC |

1.634 |

United States |

|

RBC Global Asset Management, Inc |

1.274 |

Canada |

|

Hercules Silver Corp |

14.530 |

Canada |

|

Gold Royalty Corp |

6.480 |

United States |

|

Cascadia Minerals Ltd |

7.590 |

Canada |

|

Augusta Gold Corp |

10.590 |

United States |

|

Alturas Minerals Corp |

10.800 |

Canada |

Source : https://mmeg.cnn.com

Other extractive resources include salt, hydrated sodium

carbonate, cassiterite, gypsum, tungsten, limestone, phosphate and crude oil.

The most important are salt and crude oil. The salt is mined in the

Kaouar-Manga-Dallol regions of Niger while the crude oil is exploited in eastern

and the central regions of Niger by China National Petroleum Corp[17], SONATRAC of Algeria through its international

subsidiary SIPEX, Savannah Energy[18] of the United Kingdom and China International Petroleum

Bilma. AES, through Niger, would become a significant oil and gas producer and

exporter after Nigeria given that the current appraised oil reserves is in the

neighbourhood of 3,754 million of barrels with 957 million barrels of

recoverable reserves while that of gas is 34 billion cubic metres and

recoverable reserves of 24 billion cubic metres.

Table 3: Ownership and Capital Structure of

B2Gold Corp

|

Shareholder |

% Holding |

Citizenship |

|

Bemetals Corp |

18.760 |

Canada |

|

BlackRock Investment Management (UK) Ltd |

7.316 |

British |

|

Matador Mining Limited |

6.040 |

Australia |

|

Fidelity Management & Research Co. LLC |

6.285 |

United States |

|

The Vanguard Group, Inc. |

5.917 |

United States |

|

Dimensional Fund Advisors LP |

2.755 |

United States |

|

Renaissance Technologies LLC |

2.303 |

United States |

|

RBC Global Asset Management, Inc |

1.934 |

Canada |

|

Calibre Mining Corp. |

23.930 |

Canada |

|

West African Resources Ltd |

2.160 |

Australia |

|

Fidelity Management Trust Co. |

1.421 |

United States |

|

Two Sigma Investments LP |

1.076 |

United States |

|

Two Sigma Advisors LP |

0.913 |

United States |

Source:

Agriculture

and Food Security

Agriculture

and agricultural products make up the significant sector of the AES’s economy

in terms of the number of persons employed and the percentage of gross domestic

product (GDP). In spite of the foregoing, agricultural production levels are generally low within the AES

affecting food availability and security requiring large food imports and

assistance from international donors. The farming systems are characterised by shifting cultivation, terrace farming and nomadic

herding. The main constraints to crop and food

production within the AES remain one of water, technological barriers centering

on crude and rudimentary implements as well as issues relating to soil

management.

The main agricultural crops are cotton for export, millet,

wheat,

sorghum, cassava, yam, rice, groundnuts,

tobacco, sugarcane and tea as food crops, and livestock (i.e., cattle, sheep, and goats). Just like everywhere in West Africa, crop production

is seasonal in many ecological zones of the AES constraining household food

availability and security. This is not surprising because the concentration is

on primary production and processing with very minimal secondary production in

terms of processing, and packaging into diversified food products.

The AES countries are further known to be vulnerable

to issues of climate change, loss of biodiversity, environmental hazards, low

levels of adaptability and declining agricultural

production. Some of these particularly

those related to environmental degradation are caused by crude oil exploration

and extraction by multinational companies, unbridled mineral and natural

resource exploitation by local populations and localised fuel politics. A Study

conducted in 2023 by World Food Programme and FAO predicted 3.35

million people in Burkina Faso, 3.28 million people in Niger and Mali 1.26

million people facing various degrees of acute food

insecurity and deficit

issues[19].

Infrastructure

Transportation

(Road, Railway, Air)

Currently, the three countries are not interlinked in

terms of national and transboundary road, railway and air networks. There is also proliferation of internal trade barriers

for custom goods along each constituent’s national corridors and at

international borders. These bottlenecks tend

to disrupt supply chains and movement of peoples deepening the economic

fragility of the AES countries forcing farmers and

firms to concentrate their products within the present frameworks of localized

non-networked markets.

Energy

AES, on the average, has one of the lowest rates of

electricity generation, transmission, distribution, penetration and access in

West Africa despite adequate optimal solar irradiation and the abundant endowment of large uranium and fossil fuel deposits

(crude oil & natural gas). Consequently, its energy market is still highly

undeveloped, fragmented with very little integration of national grids and

other utilities’ systems. The current penetration

rates are 53.38% for Mali[20]

generated largely from hydraulic production (%5%) and diesel (45%), 21% for

Burkina Faso, and less than 20% in Niger.

Financial

Institutions

Being in the same FCFA zone, the AES’

monetary, payments and settlements systems are much better integrated than the

anglophone and Lusophone zones of West Africa. The FCFA is tradable amongst

them and they do not have much internal constraints towards mobilization of

large domestic financial resources and financing for investment and trade. This

is about to change with the decision to move away from the FCFA zone, issue the

Alliance's own currency and establish new payments and settlements systems.

PART TWO

Conflict,

Insecurity and Population Displacement

Genesis

The main

conflict zones are concentrated in the Liptako-Gourma Region overlapping Mali,

Niger and Burkina Faso, Boucle du Mouhoun and Ménaka Regions of Mali, and the

Lake Chad Basin. The persistent conflict and worsening civil insecurity in

these zones are also the key drivers of acute food insecurity within the AES

and the cause of large population displacements. In May 2023, over 6.7 million

people were estimated to be internally displaced in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali,

the Niger and Nigeria, an increase of over 10 percent compared to the same

period in 2022[21].

The

current conflict and insecurity are traceable to the NATO invasion of Libya in

2011 and the subsequent civil war which led to dismemberment of that country.

The aftermath of the Libyan conflict led to unregulated inflow of small arms

& light weapons into the Sahara-Sahel regions (particularly, Mali, Burkina

Faso and Mali) accompanied by incursion of armed jihadist fighters. By 2012,

Mali became faced with a Tuareg insurgency led by the National Movement for the

Liberation of AZAWAD (MNLA)[22]. A fall-out of this insurgency was the

emergence of dual State and total collapse of civil institutions and public

infrastructure throughout northern Mali especially in Gao, Kidal and Timbuktu

administrative regions. After the extremist forces were expelled from northern

Mali, the Government of Mali entered into a peace deal in 2015 with MNLA and

other Tuareg groups.

However,

in 2017, AQIM, MUJAO and Ansar Dine merged to form JNIM (Jama’at Nasral-Islam wal Muslimin) and moved

its operations to central Mali after capturing Konna. It is JNIM, an affiliate

of al-Qaeda which spread the conflict to Burkina Faso in a strategic move from Konna. To become fully operational in Liptako-Gourma

Region, JNIM then entered into a new symbiotic alliance with ISGS (Islamic

State in the Greater Sahara); an affiliate of Islamic State. It was from that

time onwards that Liptako-Gourma became the hotbed for extremist violence in

the West African Sahel. Prior to the formation of the alliance through the

signing of the Liptako-Gourma Pact, JNIM was active within central and northern

Mali while ISGS has its main centres of operation located in northern Burkina

Faso[23] and western Niger.

Liptako-Gourma Region

The

region is entirely located within the semi-arid Sahel zone of West Africa and

covers the contiguous border regions of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. It

consists of 19 provinces of Burkina Faso, 4 administrative regions of Mali, and

2 departments (Téra, Say) and an urban community of Niger. With an area of

370,000 km2., the region has a topology of considerable lateritic

plateau with a general elevation of 252m above mean sea level. Given its

population size of over 18 million, the region is sparsely populated with a

population density of 48.65 persons/km2. The population is composed

of Fula, Tuaregs, Songhai, Mossi, Hausa, Gourmantche and Buzu peoples.

In terms of natural

endowment, the Liptako-Gourma Region is endowed with extensive arable land

suitable for agriculture and animal husbandry (mostly herding). It has

considerable energy resources, hydraulic and mining potential as well as

extensive transboundary ground and underground water resources covering an

estimated area of 159,000 km2. The latter is centred on the middle

basins of the Niger River. Her main mineral wealth are gold, quartz, and

manganese.

Despite

its great potential and viability, the region has since 2012 become the

epicentre of jihadist insurgency, organized crime, banditry, and illegal

cross-border operations by non-state armed groups owing to various social and

economic factors. The present lack of economic opportunities reinforced by

climatic variability has led to loss of livelihood opportunities amongst the

youth of the region. The disastrous effects of climate change on agriculture

and food security have also increased demographic pressure over dwindling

resources with the resultant dampening income effect increasing the overall

poverty level. Besides the near absence of state institutions within the region

coupled with low levels of legitimacy of State and Public Authorities in the

eyes of civil society and limited access to levels of basic public goods and

social services have also heightened communal tensions. Finally, the existence

of these voids favoured the presence of various armed non-state actors who now

provide some levels of civic services to the people.

Boucle du Mouhoun Region of

Burkina Faso

Another

epicentre of the ongoing conflict is the Boucle du Mouhoun Region of Burkina Faso. It is located along the

bend of the Black Volta River and covers an area of 34,162 km2 with

relatively rich arable lands. The region has a population of

1,901,229 (2019)[24]

of which 49.9% is below the ages of 15 years and additional 18.2% between the

ages of 15 years and 24 years. Being the poorest region of Burkina Faso with a

poverty index of 59.5%[25], it has become the hotbed

of the conflict and the centre of annual child labour exodus to cocoa and

cotton farms in Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana and Benin.

The region’s security situation has

deteriorated since the beginning of 2023 with escalating attacks by JNIM and

Ansar-ul Islam displacing tens of thousands of people from their villages and

livelihoods.

For

a long time, the Ménaka Region was the major centre of the jihadist

belligerence in Mali controlled by al-Qaeda affiliated JNIM, ISGS and the Dozo

militia. At the height of the bellicoseness, the region hosted some 78,500

internally displaced persons. The Region, which is a traditional confederacy

centre of the Kel Dinnik Tuareg tribe, is located in Mali’s northeastern Sahara

Desert border regions with Niger. The sparsely populated Region is domiciled by

nomadic Tuareg tribes, Fula and Songhai and has a total area of 81,040 km2.

Besides

being located in agroecological zone where food insecurity and poverty levels

tend to be high, this region have extensive territories that are cut off

administratively from the rest of the country. It is also denied of such basic

public goods as security, education, health and potable water which makes it

easier for JNIM to adapt local political conditions to extend its influence and

project power. It was these dehumanizing situations that Islamic fundamental

groups such as JNIM, ISGS, and various ethnic AZAWAD separatist movements

exploited by providing various levels of basic services, delivering justice

while relying on traditional dispute mediation and creating needed jobs in the

security sectors[26].

These jihadist groups also projected their power through violent means using

sabotaging or destroying of central government critical infrastructure and

implementing policies of forced displacement of local populations.

The Lake Chad Region

This

region which extends from southeast Niger, northeastern Nigeria (Yobe, Adamawa

& Bornu), western Chad to northern Cameroun is a resource poor area with

high levels of endemic poverty. Owing to the region’s degraded pastures induced

by climate chain effects, there has been keen competition over water rights

fuelling decades of internecine conflicts and insecurity. It is therefore not

surprising that the Lake Chad Region continues to witness explosion of

non-state actors be it tribal militias, cattle rustling criminal networks,

bandits specializing in kidnapping for ransom or simple highway men.

Bokom

Haram alias Jama’atu Ahl as-Sunnah li-Da’awati wal-Jihad[27]; a Nigerian Taliban group

is the main Islamic Jihad sect operating within the Lake Chad Region. As at the

close of 2023, 2.9 million people have been internally displaced. An additional

5.54 million people were also categorised as food insecure in both northeast

Nigeria and southeast Niger.

Current State of the Conflict

By

and large, the security situation across the AES’ territorial space continues

to be somewhat precarious[28] and unpredictable even

though the combined armed forces of the Alliance members had made impressive

territorial gains and pushed back several jihadist groups. With popular support of their populations, the Ménaka Region of Mali had been

liberated. The Alliance forces

also did march successfully on other several terrorist bases regaining control of most

areas while containing other actors in endemic

areas. These victories allowed schools to be reopened and resettlement

schemes implemented for good number of internally displaced population.

Despite these gains, several hundreds of

thousands of displaced populations are unwillingly to return to their villages

and livelihood due to safety reasons. One contributory factor is the limited

operational capabilities of the security forces and the ineffective roles of

their allied auxiliary Volunteer Militias[29]. It is worth-mentioning that in the case of

Burkina Faso, the 50,000 strong forces[30] were formed out of two

ethnic-based private militias of the Koglweogo and Dozo and instead of being an

inclusive force of arm, it carried out operations along ethnic lines committing

and carrying out extra-judicial arrests, killings, rape and torture. So far,

the security authorities’ dual purpose of controlling activities of these

auxiliary forces and using them as vehicles to mobilize and defeat the

insurgents have not been met.

Since the close of 2021, the Alliance forces have reorganized under

single command with superior improvements in tactical planning and support from the Russian Wagner Group[31] and

are currently on the offensive. The present turn of events can be attributed to

the military juntas’ re-prioritization of security and the setting up of

Patriotic Support Fund in which citizens made direct contributions towards

prosecution of the war effort. Another contributory factor was the smart

financing strategy adopted by the military junta of each member country.

Subsidies, for instance, were removed on petroleum and other consumptive goods

and the savings made were used in procuring military equipment, munitions and

other war materials from Turkey, Russia, North Korea and China. With the Russians leading the

pack, there were increased access to better situational intelligence. Besides, as a result of ascendancy in

patriotism driven by anti-French feelings, the people of the Sahel were more

willing to mobilize and defend their territorial spaces.

The Jihadist Rebellion

It would be

recalled that the strategic objective of the jihadist rebellion in the Sahel

besides holding, capturing and/or expanding territory is to secure new recruits

so as to replenish its ranks and file. The withdrawal of French troops and

MINUSMA from conflict zones[32]

and the initial weak logistic support condition of the Malian Security &

Defense Forces in the early 2020s provided the keg to the re-occupation of

territorial spaces in Mali and Burkina Faso in particular. The jihadist also

took advantage of opportunities offered by numerous inter-communal conflicts

and general prevalence of political instability following the NATO invasion of

Libya.

However, the tides

had changed since the announcement and implementation of the military alliance.

The first casualty was the decision of Coordination of Movements of AZAWAD to

withdraw from the implementation of the 2015 Peace Plan following the failure

of the Mali’s military junta to commit to an electoral calendar and provide

definite date of handing over to a democratically elected government. This led to the collapse of the Algiers Accord of

2015.

The Algiers peace agreement for Mali remains incompletely implemented. It is

worthy of note that the parties have never implemented the substantive

regionalization reforms defined in Sections I & II of the Agreement which

laid out the political and institutional autonomy of the Northern Regions.

Following their

defeat in central and northern by the Alliance Forces, the jihadist rebellion

is now stymied and on the backfoot.

Foreign Military Presence in

AES

An outcome

of the NATO’s intervention in Libya was the incursion of Islamic State’s

fighters into the Sahara-Sahel Region accompanied by the establishment of

jihadist terrorist cells. This led to France in 2013 sending its expeditionary

forces into Mali under Operation Serval to counteract them. This singular act

opened the door for foreign Military Presence in West Africa. France was

followed by other members of the European Union namely Germany, Italy and

Belgium, the United States and United Kingdom.

It would

be recalled prior to the Alliance,

there were six foreign countries that have and operate land (9), air (10) and

naval (1) bases[33]

in West Africa. France and the United States dominate with presence in five

West African countries respectively. The US is present in Niger, Burkina Faso,

Senegal, Ghana and Nigeria whiles France is in Mali, Cote D’Ivoire, Senegal,

Burkina Faso and Niger. Germany has bases in Niger and Mali whiles Italy and

the UK are present in Niger, Mali respectively. Finally, Belgium has a base in

Mali.

Currently, with the popular support of their

various populations who demanded the closure of French bases and withdrawal of

her troops from the Alliance’s member countries, France had withdrawn her

troops and closed her bases in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. This was

followed by the closure of Belgian, German, Italian and British bases as well

as the withdrawal of UN Peacekeeping Forces (MINUSMA) at the close of 2023. As

could be expected, the Nigerien Authorities in February declined to renew the

leases of the American bases. It is not known whether the US will be removing

its military bases from Niger.

The Role of Wagner Group of

Russia

The Wagner Group of Russia has

played a crucial role in steadying and restoring the territorial integrity of

the AES countries. The various constituent governments have signed separate

military pacts with Russia[34] and

went on to deploy personnel, tactical vehicles and war materials to strengthen

the strategic capacities and operational capabilities of the Alliance armed

forces. The Wagner Group has some 3,000 mercenaries including instructors

deployed in Central Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger where they are currently

fighting insurgency groups. The group also provides tactical support in terms

of operational planning. For now, there are no Russian boots on the ground.

State

of the Alliance[35]

It is

worth-mentioning that the current Military Pact is not the first ever mutual

defence pact signed by the three countries. In 2017, Mali, Burkina Faso and

Niger had a similar agreement in which they established a joint task force to

confront jihadist insurgency threats including general insecurity within the

Liptako-Gourma Region[36]. The current pact

therefore seeks not only to revive the defunct agreement and provide united

front to confront the threats of potential external aggression or internal

armed rebellions but also aimed at responding to the ECOWAS threat to intervene

militarily in Niger. It would be recalled that following a military coup led by

the Presidential Guards, which overthrew the legally elected President Mohamed

Bazoum of the Republic, ECOWAS provoked a Nigerien Crisis in a bid to restore

constitutional rule.

It would

further be recalled that apart from the Alliance members being in a state of

low armed insurgency since 2003 from communal tensions, jihadist strife,

constitutional coups by politicians and military coup d’états; there has also

been significant displacement of population. By August 2023, the total number of persons

displaced was 2,948,799[37].

The future

of the Alliance would depend on how early minimum security and sovereignty

could be restored throughout the territory of the alliance. It would also

depend on how long will the current military juntas want to clasp to power. All

told, there is the likelihood of a new model of governance and sharing of power

emerging through a conscious development of popular organs, institutions and

vanguard of the people. This may also include successful de-institutionalising

of current bourgeois elective and representation systems; and building

self-reliant planned economies through the control and judicious use of

appropriated endowed resources. It would also mean moving away from the present

neocolonial arrangements and relations towards political integration and

building a Pan-Africanist AES which is broadly anti-imperialist. Finally, this

would require providing an entry in the present Charter for other countries,

within or outside West Africa, seeking genuine sovereignty and African Unity to

freely elect to join.

Meanwhile, there are efforts to withdraw from

the FCFA monetary zone and to print the Alliance’s own currency to be known as

the “Sahel” in addition to establishing a own central bank to be in charge of

the Alliance’s monetary policy.

The ECOWAS Web

Since the overthrow by the military of the

constitutions and lawful civilian governments in the three countries, there has

been several ECOWAS’ reactions and grandstanding over the unconstitutional and

illegal interventions. The alliance members, for instance, have been suspended

from ECOWAS and various levels of punishing sanctions imposed. These sanctions

are supported by the AU, EU, US, and UN. At one stage, ECOWAS threatened to

invade Niger and to restore the constitutional authority of President Bazoum.

So far, attempts to use diplomatic means to resolve the standoff have failed

owing to the stance taken by ECOWAS. Subsequently, the Alliance States have

exited[38] ECOWAS[39].

CONCLUSION

L'Alliance des

États du Sahel (AES) created in September 2023 by Mali, Burkina Faso

and Niger is essentially a military cum economic accord. There will also be the

need to enter into some political union tailored along the lines of confederacy

with clear-cut constitution and devolution of power. Such a road will require

ideological clarity of the current leadership, massive mobilisation of popular

forces within the AES and reformation or building of new institutions that are

people-centred. It will also be imperative to raise the current low social

consciousness prevalent and working diligently to secure the material

well-being of the mass of the people.

REFERENCES

ECOWAS Commission. The West African Food Security

Storage System: Synthesis of lessons learnt and perspectives. 2021. https://www.google.com/search?q=handling+and+storage+issues+in+west+africa+agriculture&oq=handling+and+storage+issues+in+west+africa+agriculture&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIHCAEQIRigATIHCAIQIRigAdIBCTM1OTgyajBqN6gCALACAA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

FAO.

2023. Crop Prospects and Food Situation – Quarterly Global Report No. 2, July

2023. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc6806en; https://dtm.iom.int/report-product-series/liptako-gourma-crisis-monthly-dashboard

FAOSTAT and Agriculture Statistics Directorate -2021; https://www.wfp.org/news/food-insecurity-and-malnutrition-west-and-central-africa-10-year-high-crisis-spreads-coastal# ; Djaounsede.madjiangar@wfp.org

Lloyd,

Robert B. “Ungoverned Spaces and Regional Insecurity: The Case of Mali.” The

SAIS Review of International Affairs, vol. 36, no. 1, 2016, pp.

133–41. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27001424.

Accessed 25 Oct. 2023.

MALI Violence

in Ménaka and Gao regions - ACAPS, Thematic Report, 16 June 2022 https://www.acaps.org/fileadmin/Data_Product/Main_media/20220616_acaps_briefing_note_violence_in_mali.pdf

Non-State Armed

Groups and Illicit Economies in West Africa: JNIM, October 18, 2023 ACLED ; GITOC;

https://dtm.iom.int/report-product-series/liptako-gourma-crisis-monthly-dashboard

2023 West Africa Economic Outlook; July 27, 2023, https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/2023-west-africa-economic-outlook-regions-economic-growth-falls-medium-term-forecast-suggests-return-level-above-4-63487

Vilar

(ed) (2012) ‘Renewable Energy in Western Africa: Situation, Experiences and

Trends’, ECREEE and Casa Africa www.ecreee.org/sites/default/files/renewable_energy_in_west_africa_0.pdf

Willemien

Viljoen, “Transportation costs and efficiency in West and Central Africa” https://tralac.org/discussions/article/9364-transportation-costs-and-efficiency-in-west-and-central-africa.html

Orano, Consolidated Financial Statements, Dec.31, 2022; https://cdn.orano.group; https://www.orano.group

Orano Canada Inc., 26 April 2023; https://mscf.ca/ckfinder/userfiles/orano%20canada%20-%lewsi%20Haddad%20FINAL%20correction.pdf

https://mscf.ca>OranoCanada-Jim Gorman PDF, 17April 2024

https://www.b2gold.com>Q4-FS-2023 pdf

https:www.b2gold.com>_resources>financials pdf; Mar.2020

https://www.b2gold.com>B2Gold-AIF-2023 pdf

https://fintel.io>US>B2Gold Corp

[1] The only country not covered is the island State of Saint Helena.

[2] At present, anti-French sentiments have heightened transforming

these military interventions into popular struggles for national sovereignty

and independence.

[3] Currently, all the AES countries are ruled by

military juntas and are under various forms of economic sanctions imposed by

ECOWAS, AU, EU and UN.

[4] The contiguous territory of AES and size has provided a competing

geopolitical threat to ECOWAS; the regional economic community.

[5] France’s Presse Agency and France24 media were also

asked to discontinue their media presence and leave the respective territories.

[6] AES currently has 5% of the world’s uranium reserves or some

311,100 tons U

[7] Following the restructuring and recapitalization of the nuclear

conglomerate AREVA, it was renamed ORANO S.A. ORANO, which is headquartered in

France, is in uranium mining, conversion, enrichment, spent-fuel recycling and

nuclear engineering activities.

[8] Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique et

aux énergies alternatives (CEA)

[9] Banque Publique d’Investissement (Bpi)

[10] It is worthy of note that France throughout the period

until the sovereign coup d’etat in June/July 2023 had bought Nigerien uranium

at a rate of €0.80 per kilogram compared with €200 per kilogram she had paid

for similar uranium from Canada. It was therefore not surprising when the first

action of the Nigerien Authorities had to do with increasing its selling rate

to €200 per kilogram.

[11] There are over 350 artisanal mines in the three countries

constituting the AES at the end of 2023 employing a little over 500,000 direct

mine workers.

[12] Founder of Barrick Gold Corp is Peter D. Munk

[13] Barrick Gold Corp owns 80% of the capital of Société de Mines des

Gounkoto and Société de Mines de Loulo SA respectively while the remainder in each

company is owned by the Malian State. Both mines have a proven reserve of 6.7

million ounces of recoverable gold. In 2022 alone, both mines produced 547,000

fine ounces of gold

[14] Founder of B2Gold Corporation is Clive Johnson

[15] IAMGOLD is founded by Mark I. Nathanson and William D. Pugliese

[16] Burkina Faso, a constituent member of the Alliance, has

taken steps to address this through building a gold refinery.

[17] China National Petroleum Corp produces 20,000 b/d of crude oil at

the Agadem Rift Basin through a consortium comprising OPIC (a wholly owned

subsidiary of CPC Corporation of Taiwan and the State of Niger.

[18] Savannah Energy operates also in the crude oil and gas sectors of

Nigeria, Cameroon and South Sudan. It currently has exploration license in

Niger within the Amdigh, Eridal, Bushiya, Kumana oil reserves where it intends

bringing up to four oil wells on stream in 2025.

[19] Source: FAOSTAT and Agriculture Statistics

Directorate, 2021

[20] The total installed capacity from hydro production and solar is 310

MW

[21] Source: FAO. 2023. Crop Prospects and Food Situation –

Quarterly Global Report No. 2, July 2023. Rome.

https://doi.org/10.4060/cc6806en

[22] It would be recalled that the MNLA had earlier on

allied with Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Movement for Unity and

JIHAD in West Africa (MUJAO) and Ansar Dine to occupy and declare an

independent state of AZAWAD in northern Mali.

[23] ISGS initial operation

in Burkina Faso was in September 2016 after attacking and controlling a border

post near the city of Markoye.

[24] Estimated population for 2024 is

2,120,626 and a population density of 55.65 persons/km2

[25] The mean national

poverty index is estimated at 40.1%

[26] Of course, the objective is to run parallel underground

economies for the generation and financing of war operations and to establish

alternative governance systems. These largely take the form of imposing and

collecting taxes in the gold mining operations under their sphere of influence.

[27] The group has recently increased its attacks in and

around Maiduguri as well as weaponisation of food resulting in loss of lives,

livelihoods and displacements of local populations.

[28] In the

case of Burkina Faso, the jihadists’ insurgents breached more than half of her

territorial integrity.

[29] The VDF

(Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland) was reorganized at the beginning

of 2023 along the concept of popular defence by the present military junta

under the leadership of Colonel Kabore and given 14-days military training.

[30] 35,000 of the auxiliary

force has been assigned to protect the local communities while the remainder of

15,000 have been integrated into the country’s security and defense

architecture.

[31] The Wagner

Group is a Russian private and private

military auxiliary force consisting of ex-servicemen with extensive combat

experiences who offer their services for money. As a quasi-state armed group,

it has several presence in Africa notably Central African Republic and Sudan

and oftentimes used by the Russian Government to executes its geopolitical

objectives.

[32] The pull-out of French Expeditionary Forces in October

2022 which brought Operation Barkhane to an end created a military and security

vacuum in the theatres of operation.

[33] Key military operations

carried out by these foreign military bases include training and technical

assistance, logistics support, anti-piracy operations, intelligence and

surveillance operations, and peacekeeping missions.

[34] The relationship with the Alliance States is

strategic. Traditionally, the armed forces of the Alliance members have 80% of

their military arsenals imported from Russia and North Korea. This relationship

dates back to the late 1970s. This is because Russians, unlike the French and

the West, have no curbs or restriction on export of military hardware or

ammunitions and are willing to sell every type of armament to third parties

provided there is an effective demand.

[35] The essence of the current

l'Alliance des États du Sahel (AES)

pact, as stated, is to stave ‘armed rebellion or external aggression’ off and

protect any of the members of the alliance from threats of possible overthrow

from ECOWAS and imperialist France especially as ‘any attack on the sovereignty

and territorial integrity of one or more contracted parties will be considered

an aggression against the other parties.’

[36] The task force, at then, was part

of the multinational force of the G5 Sahel countries comprising forces drawn

from Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad. Mali, however, withdrew

from the G5 Alliance in May, 2022. It is worthy of note that the G5 Sahel was

an institutional framework within which the Alliance members coordinated

regional development policies and security matters especially those relating to

jihadist insurgency threats of AQIM, MOJWA, Al-Mourabitoun and Bokom Haram.

[37] This constituted 98% of the internally displaced

population. Out of the internally displaced

population, 71% were located in Burkina Faso while Mali,

Niger and Mauritania had 15%, 9% and 3% respectively. A further 321,669

representing 2% of the displaced population spilled over to Cote d’Ivoire,

Ghana, Togo and Benin as refugees.

[38] On 27th January, 2024,

the three member countries of the AES simultaneously announced their respective

exit of the Community. As a consequence, ECOWAS has lost some 44.5% of its land

mass and about 17% of its citizens. Other implications of these exits would include

massive disruption in south-north trade and disruption of current supply

chains, lack of access to seaports located along the coasts of Côte d’Ivoire,

Ghana, Togo, Benin and Nigeria as well as likely intensification of

geopolitical rivalry of great powers. Meanwhile, the Kingdom of Morocco has

offered to provide the AES access to its seaports.

[39] It is

worthy of note that since the exit of Mauritania in December 2000 and her

return in 2017 as an associate member of ECOWAS, no other country has exited

from the community.

Comments

Post a Comment